Sexual harassment usually is something an individual has endured alone. The #MeToo movement has given a community to those discouraged, afraid, or otherwise reluctant to share their stories. This led many people to come forward about past or current cases of sexual harassment, violence, or abuse that probably would not have done so in the past. It also illuminates the pervasive culture that surrounds us: if viewed as a broad, societal trend rather than a collection of individual incidents, we see that there are certain environmental factors regarding organizational climate and norms that allow these incidents to occur.

The Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces (ICHW) conducted a study last year to identify environmental risk factors to aid the refinement and development of sexual harassment prevention efforts in institutions of higher education. Specifically, ICHW collected anonymously reported narratives from individuals in higher education who have experienced and/or witnessed sexual harassment. The data were collected for the PATH to Care Center at UC Berkeley, who is using this information to create a preventive “tool kit” for academic departments. This program is designed to guide decision-makers in a plan to prevent sexual harassment in their academic communities. The PATH to Care Center drew from both the existing prevention literature and our findings. After finishing my work with the ICHW study, two main themes have stuck with me: bystander responsibility and the barriers to reporting sexual harassment in higher education—not just at UC Berkeley:

Bystander Non-Intervention

Out of the sexual harassment incidents collected through the ICHW study, over half involved bystanders: yet only 1 in 5 the bystanders actually intervened. Whether they didn’t care, didn’t feel empowered, or simply didn’t recognize what was happening, our data illustrate an unfortunate, prevalent trend: bystanders are unlikely to intervene in cases of sexual harassment. This corroborates a large body of literature, as the bystander effect has been extensively studied in psychology and neuroscience.

Barriers to Reporting

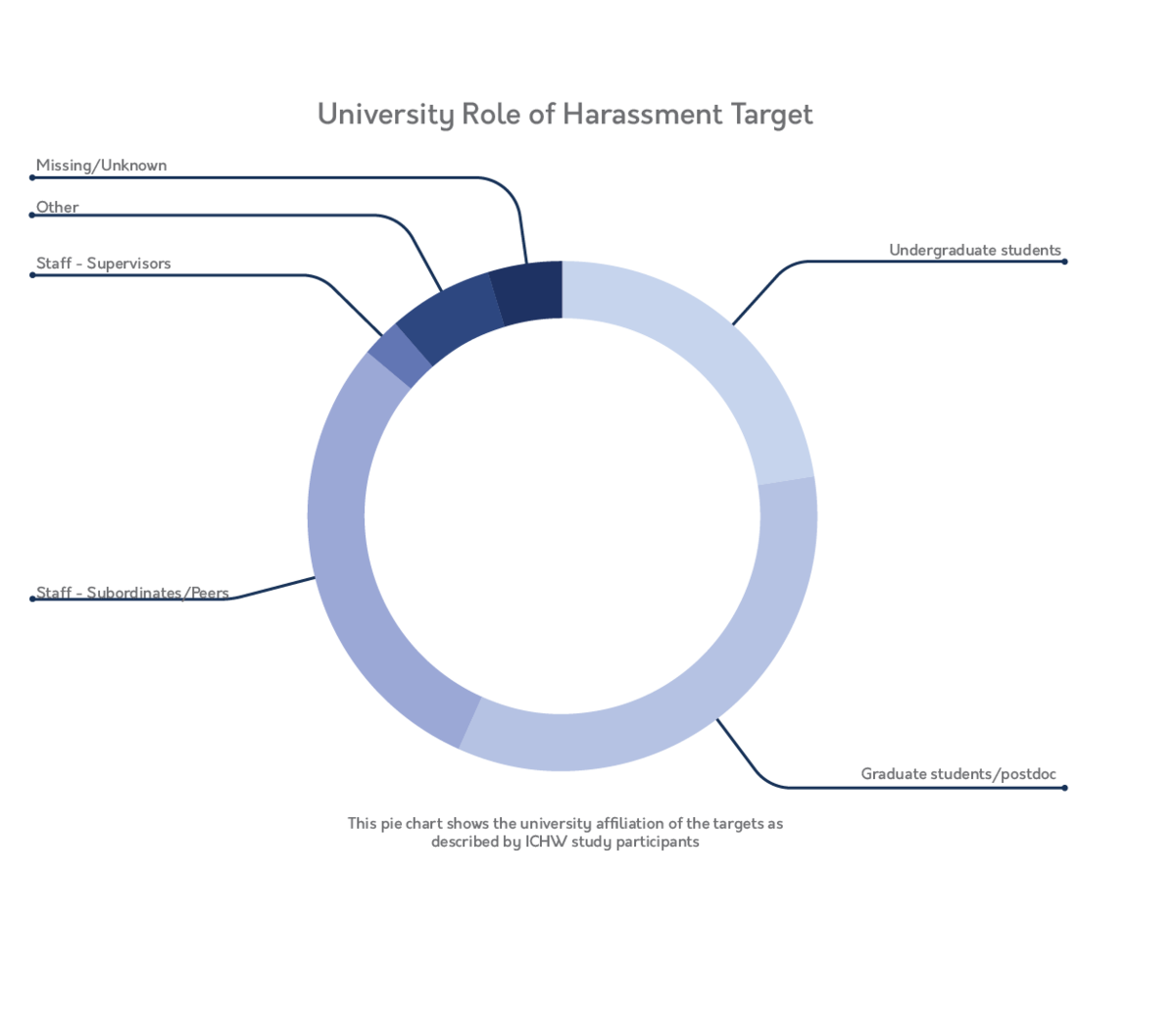

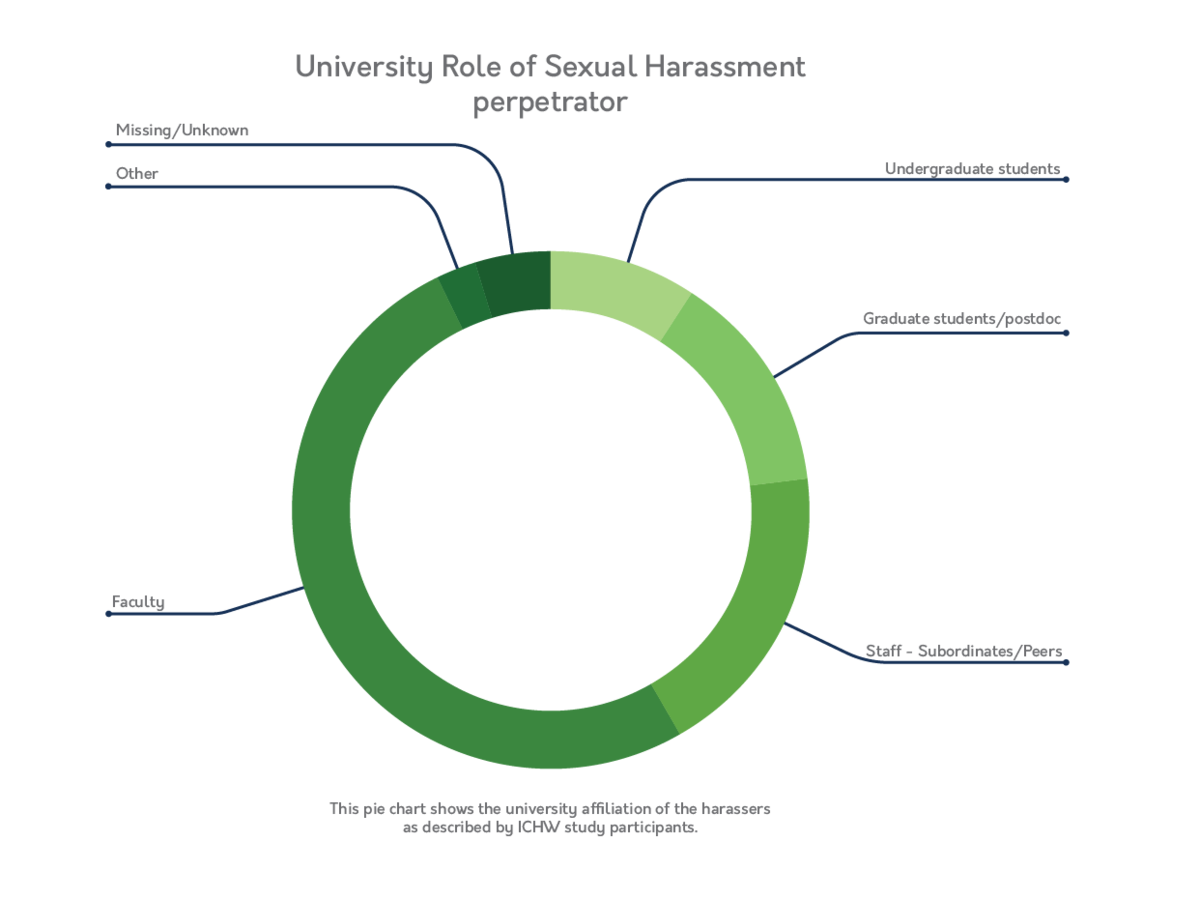

Our findings also illustrated a broader trend regarding barriers to reporting instances of sexual harassment in higher education. The ICHW report maintains that “quite a few study participants… made a conscious decision not to report the incident because they… believed reporting would result in a lack of support and social and professional retaliation.” This means that even if official procedures and protocols for reporting are made clear, it can be difficult to effectively report and hold harassers accountable for their actions. The power differential often seen between harassers and targets decreases the chances of successful reporting and repercussions. For example, the ICHW study found that the vast majority of harassers in higher education were faculty rather than students or staff, as shown in the figure below. Harassers should be held responsible for their actions: the school and administration must handle the situation fairly and justly by mitigating the barriers to reporting and support. Failing to do so propagates a toxic institutional culture, both inside and outside of higher education.

A Path Forward: Safe Spaces and Community Support

Although traditional interventions, such as harassment prevention trainings, can address environmental factors, another preemptive—ameliorative—strategy can be the creation of safe spaces and community support. These can provide individuals with social support and empower them to be active bystanders. Over time, a supportive community culture can normalize incident reporting. Taken together, these community spaces address bystander non-intervention and under-reporting as described above.

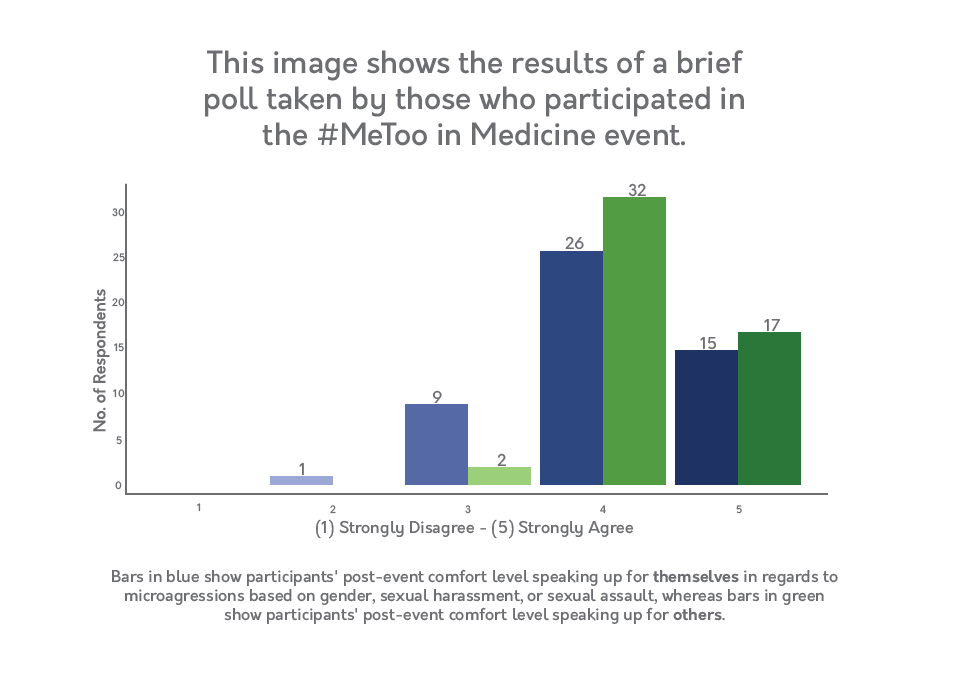

Earlier this semester, I came across an event titled #MeToo in Medicine, an exemplar of a supportive, healing space for those affected by gender discrimination in higher education Specifically, the purpose of the event was to “bring together UCSF health professionals to share anonymous stories related to the theme of gender disparities for the purpose of strengthening community.” Hearing the narratives of those experiencing discrimination and harassment is an incredibly educational and moving experience. I then realized that creating a safe space for these narratives is a difficult but necessary prerequisite to fostering a safer, more inclusive environment. To learn more behind the how and why of the event, I reached out to one of the UCSF medical student organizers, Nazineen Kandahari

My personal experience with the ICHW study parallels Kandahari’s motivations for organizing the #MeToo in Medicine event. A few weeks before starting medical school, she heard her future classmates talk about sexual harassment prevalent in many medical institutions, advising her to prepare for gender-based harassment and violence. Surprised and frustrated at the notion of “bracing herself” for violence, Kandahari searched for a real solution:

“I wanted to create a space that honored these voices, where people felt safe to share, hear, learn from, and support each other. My goal was to honor survivors while also educating others on what gender-based violence looks and feels like and different ways of responding should they ever witness or experience acts of violence. Ultimately, I wanted to build the foundation for a support system.”

Although our socio-cultural landscape is shifting towards and normalizing the sharing of these narratives in terms of community with the #MeToo movement, it is still incredibly difficult for someone to come forward about their experience, especially if the perpetrator is someone in power. This goes back to the barriers to non-reporting we found in the ICHW study: the power differential between the harasser and the target is one of the greatest reasons these incidents aren’t reported. While it can be difficult to navigate these systems on our own, it is our prerogative as members of this—and any—community to demand more from our administration, be active bystanders, and educate ourselves on how to be there for people who have experienced harassment, individually and as a community. These action steps apply to those in power especially: sticking to the status quo is what’s comfortable, but standing up for what is right ultimately makes individual lives, organizational culture, and societal norms better overall.

Starting conversations and raising awareness on how to be a good ally are also critical actions steps for creating a safer and more inclusive environment. In addition to the anonymous narrative readings, #MeToo in Medicine partnered with Bay Area Women Against Rape (BAWAR) to hold a training on empowering survivors of sexual violence. Seminars like these inform community members who may be unsure of the best way to support targets of gender-based discrimination or support the movement in general.

“For those who have the power to advocate for others, inaction is an action,” Kandahari says firmly. “Not speaking up for others when they have the power to is a choice.” She mentions that working with two of her male-identifying colleagues solidified her belief that culture change can’t happen just from targets speaking up: it has to come from people of privilege recognizing their power and are willing to be allies in solidarity to people affected by sexual harassment or violence.

“It was great to hear from their perspective,” she explains. “And to hear how we can get more of those people who aren’t affected by it yet—or hopefully ever—to learn to support survivors and start a greater cultural change that can lead to policy change.”

Conclusions

My experience processing the ICHW study data was incredibly powerful because I simultaneously saw the impact these incidents had on individual lives and the common denominators that underscored these testimonies. As a woman, these stories resonated with me because I plan to stay in the higher education environments for the foreseeable future. Before researching the topic myself and my conversation with Nazineen Kandahari, I didn’t really know how to be a good ally to people who have experienced sexual harassment or violence. Lastly, I learned how important having community support really is. There is a network of people who will support you as an individual and work towards a world where what happens to you will never happen to anyone else again